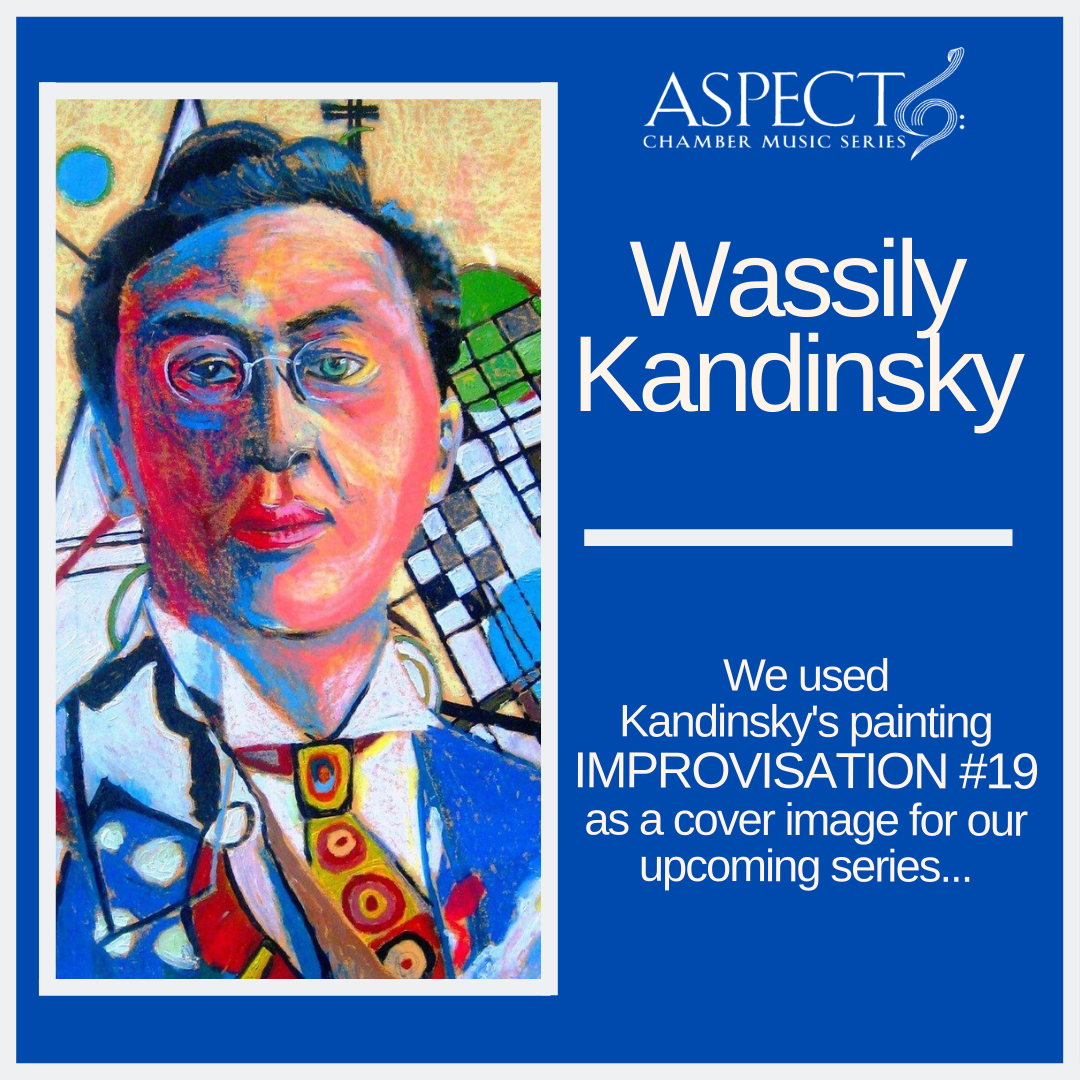

WASSILY KANDINSKY: PAINTING WITH COLOUR & MUSIC

Our longtime collaborator Patrick Bade comments on our cover image for MUSIC IN THE TIMES OF CRISIS: Kandinsky’s Improvisation #19.

According to the famous dictum of the nineteenth-century aesthete Walter Pater, “All art constantly aspires to the condition of music”. Around the turn of the twentieth century, this idea was taken up by many – including the Russian artist Vassily Kandinsky – and played a key role in the early development of modern art.

Kandinsky himself wrote, “Colour is the keyboard, the eyes are the hammers, the soul is the piano with many strings, the artist the hand which plays, touching one key or another, to cause vibrations to the soul.” It was a performance of Wagner’s Lohengrin at the Bolshoi Theatre in Moscow in the 1890s that had awakened him to the power of art and to the connection between sound and colour: “I saw all my colours in my mind; they stood before my eyes. Wild, almost crazy lines were sketched in front of me. It became quite clear to me that art in general was far more powerful than I had thought, and that painting could develop just such powers as music possesses.”

Kandinsky’s Improvisation 19 dates from 1910, the year before the publication of his seminal essay Concerning the Spiritual in Art, which mapped out his journey towards abstraction, a journey paralleled by that of Arnold Schoenberg towards atonality, as we find documented in the fascinating correspondence between artist and composer from the years 1910–14.

As World War One approached, there were several artists whose antennae seemed to pick up on a mood of impending crisis or even catastrophe. Ludwig Meidner’s apocalyptic Berlin landscapes, for example, seem to predict with uncanny prescience not only the devastation of the Great War but the physical destruction of that city in the Second World War. A sense of foreboding is also conveyed by the increasing agitation discernible in the work of both Schoenberg and Kandinsky – in the former’s First Chamber Symphony, for instance, and in the latter’s Composition VII and Improvisation; Deluge, both of which date from 1913.

Prepared by Longtime Friend and Collaborator, Patrick Bade

Patrick Bade is an historian, writer and broadcaster. He studied at UCL and the Courtauld and was senior lecturer at Christies Education for many years. He has worked for the Art Fund, Royal Opera House, National Gallery, V&A. He has published on 19th- and early 20th-century painting and on historical vocal recordings. His latest book is Music Wars: 1937–1945.

www.martinrandall.com/patrick-bade