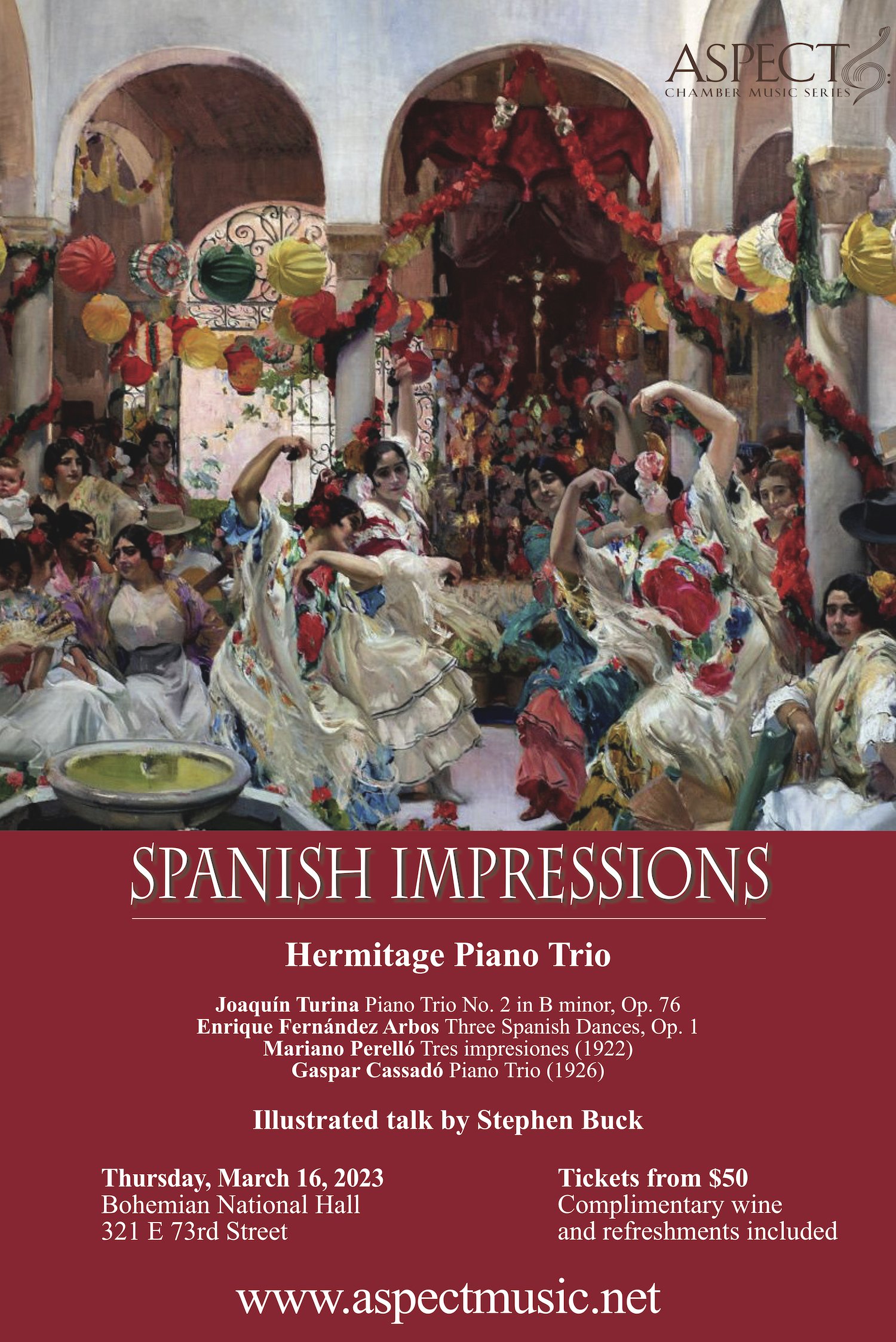

SPANISH IMPRESSIONS

March 16, 2023 | Bohemian National Hall

Hermitage Piano Trio

Misha Keylin, violin

Sergey Antonov, cello

Ilya Kazantsev, piano

Illustrated talk by Stephen Buck

Program

Joaquín Turina Piano Trio No. 2 in B minor, Op. 76

Enrique Fernández Arbos Three Spanish Dances, Op. 1

Mariano Perelló Tres impresiones (1922)

Gaspar Cassadó Piano Trio (1926)

Photographs by Alex Fedorov © 2023

From El Greco to Gaudí, Spain has often produced cultural figures whose work seems extreme and eccentric. Its national identity was forged in the bitter struggle between Christian and Islamic forces in the later Middle Ages. In 1492 Christianity triumphed, in an extreme and radical form, but traces of Islamic and Jewish heritage remained in the DNA of Spanish cultural heritage, particularly as far as music was concerned. And from the Inquisition to the Civil War, Spain has seen more than its fair share of man’s inhumanity to man. Yet the work of artists such as Velázquez, Goya and Picasso, and writers such as Cervantes and Lorca, is notable for its humanity. After a long period of decline, culminating in 1898 in humiliating defeat at the hands of the United States and the loss of her colonial empire, Spain enjoyed a brilliant cultural renaissance that lasted until the outbreak of the Civil War in 1936. This programme will showcase some of the varied and brilliant music composed during that period.