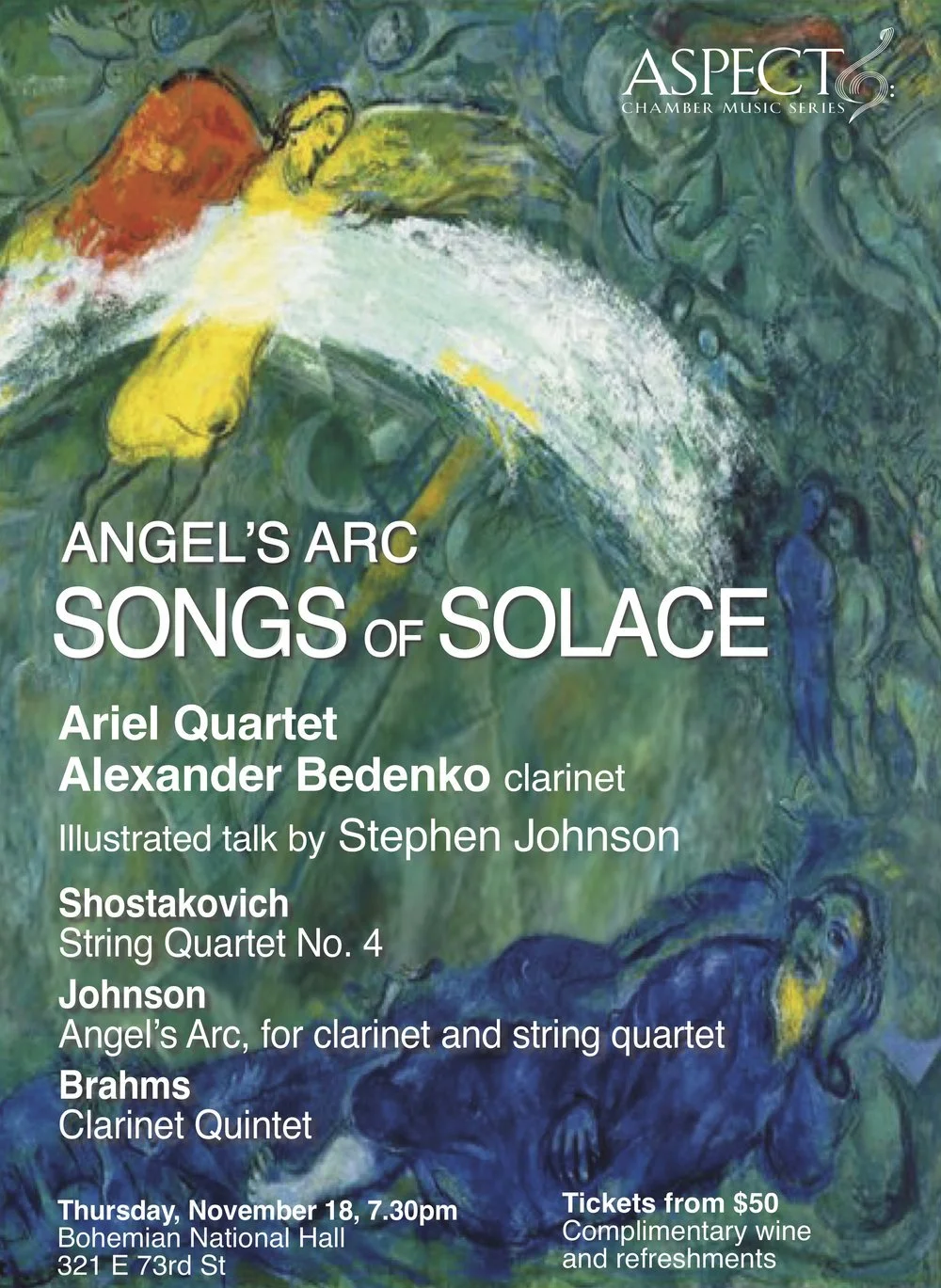

SONGS OF SOLACE

November 18, 2021 | Bohemian National Hall

Ariel Quartet

Alexander Bedenko clarinet

Illustrated Talk by Stephen Johnson

PROGRAM

Shostakovich String Quartet No. 4

Stephen Johnson Angel’s Arc, for clarinet and string quartet

Brahms Clarinet Quintet

Photographs by Tao Ho © 2021

The Russian composer Dmitri Shostakovich loved Jewish folk music, delighting in what he called its ‘laughter through tears,’ and he turned to it during one of the worst crises in his roller-coaster career. His Fourth String Quartet is full of anguish and heartache, but in the klezmer dance-like finale it reveals how Shostakovich found the strength to keep going and, as a friend put it, ‘keep bearing witness.’ A work-weary Johannes Brahms announced his official retirement from composition at the age of 57, but the following year the playing of clarinetist Richard Mühlfeld charmed him back, and a string of beautiful, profoundly personal masterpieces followed. In the glorious Clarinet Quintet Brahms expresses his regrets, his melancholy, but also his intense love of life in new confidential terms – it’s as though the music were speaking to a small group of close, loving friends. Alongside these two gems of the chamber repertoire, we are delighted to present the US premiere of Stephen Johnson’s clarinet quintet Angel’s Arc. The work was inspired by the hills of Northern England where, as a troubled, isolated teenager, the composer found a place of refuge and strength. Angel’s Arc is a hymn of gratitude to the mysterious but very real sustaining power of nature and of music.