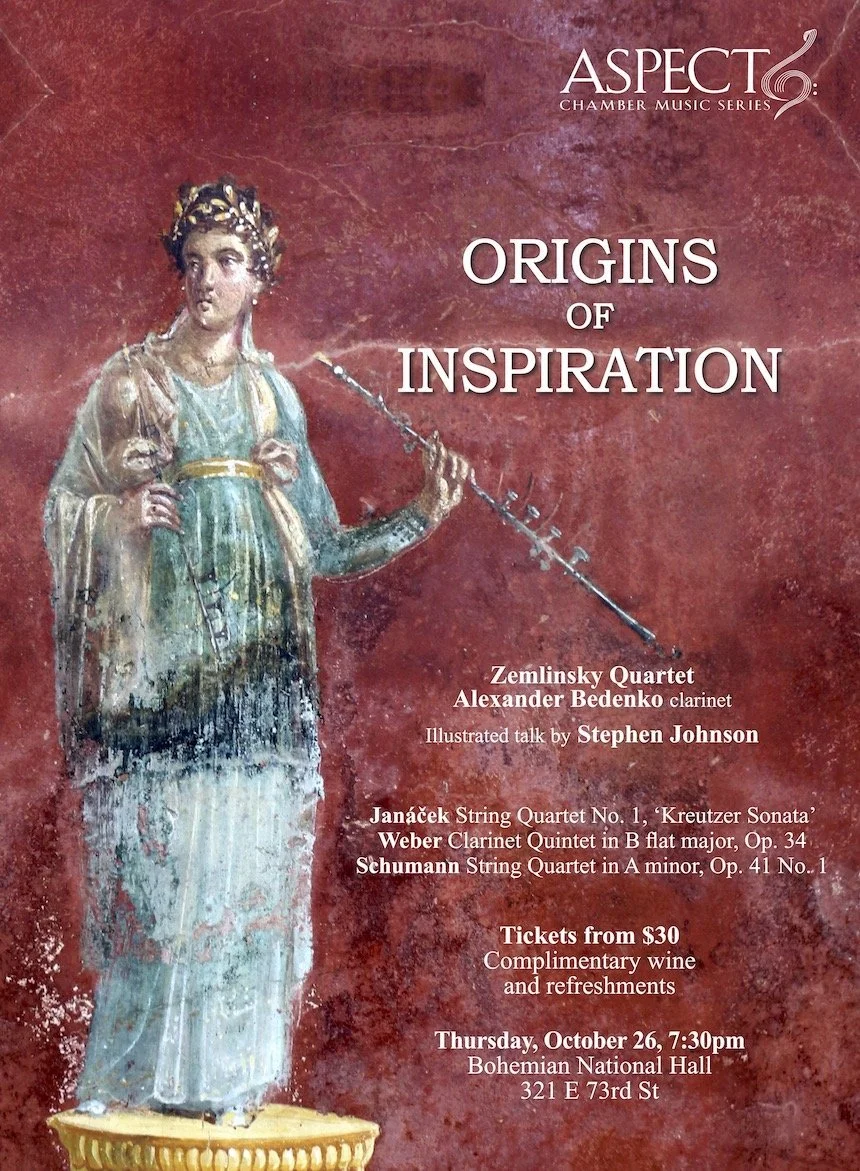

ORIGINS OF INSPIRATION

October 26 | Bohemian National Hall

Zemlinsky Quartet

Alexander Bedenko clarinet

Illustrated talk by Stephen Johnson

Program

Janáček String Quartet No. 1, ‘Kreutzer Sonata’

Weber Clarinet Quintet in B flat major, Op. 34

Schumann String Quartet in A minor, Op. 41 No. 1

Photographs by Alex Fedorov © 2023

What inspires an artist? ‘Divine madness’ or ‘possession by the muses’? Greek antiquity attributed prowess in music to Euterpe, the muse whose role it was to assist composers in their work. Yet surely there must be a more tangible explanation? Love, friendship, nature, and literature are all potential sources of profound inspiration. Who was it that so impressed Carl Maria von Weber that he produced a flood of pieces for him? Why is Robert Schumann’s String Quartet in A minor dedicated to the phenomenally gifted Felix Mendelssohn? What moved Leoš Janáček to write one of the most dramatic and ferociously impassioned creations in the entire chamber repertoire? We invite you on a fascinating journey to discover what led each of these three composers to write the works featured in this program.