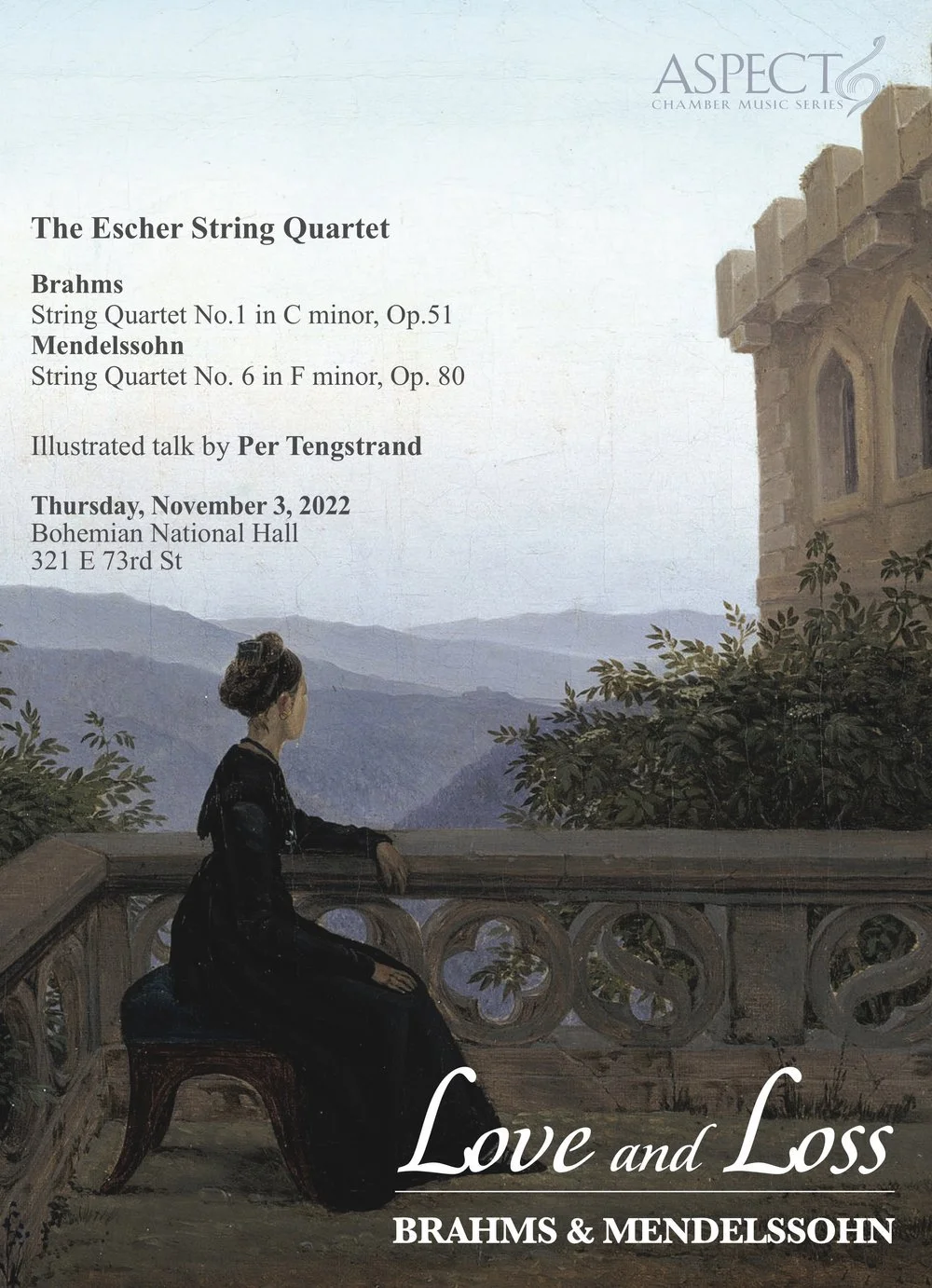

LOVE AND LOSS: BRAHMS & MENDELSSOHN

November 3, 2022 | Bohemian National Hall

Adam Barnett-Hart, violin

Brendan Speltz, violin

Pierre Lapointe, viola

Brook Speltz, cello

Illustrated talk by Per Tengstrand

PROGRAM

Brahms String Quartet in C minor, Op. 51 No. 1

Mendelssohn String Quartet in F minor, Op. 80

Photographs by Alex Fedorov © 2022

Brahms and Mendelssohn both wrote impressive works for the grand concert hall, but their chamber works take us into their secret hearts. When Brahms began work on his C minor Quartet, he was still struggling with the impact of his mentor Robert Schumann’s final descent into madness, and with his intense but complicated feelings for Schumann’s widow Clara. By turns stormy, achingly tender, and haunted, this work sounds very like the lonely cry of a wounded soul. Mendelssohn’s F minor Quartet was composed in stunned grief after the shockingly premature death of his beloved sister Fanny. If at times it seems close to breaking point, that may be a simple statement of fact: Mendelssohn himself died just two months after finishing it. But at its heart is a song of pure love, perhaps the tenderest he ever composed.