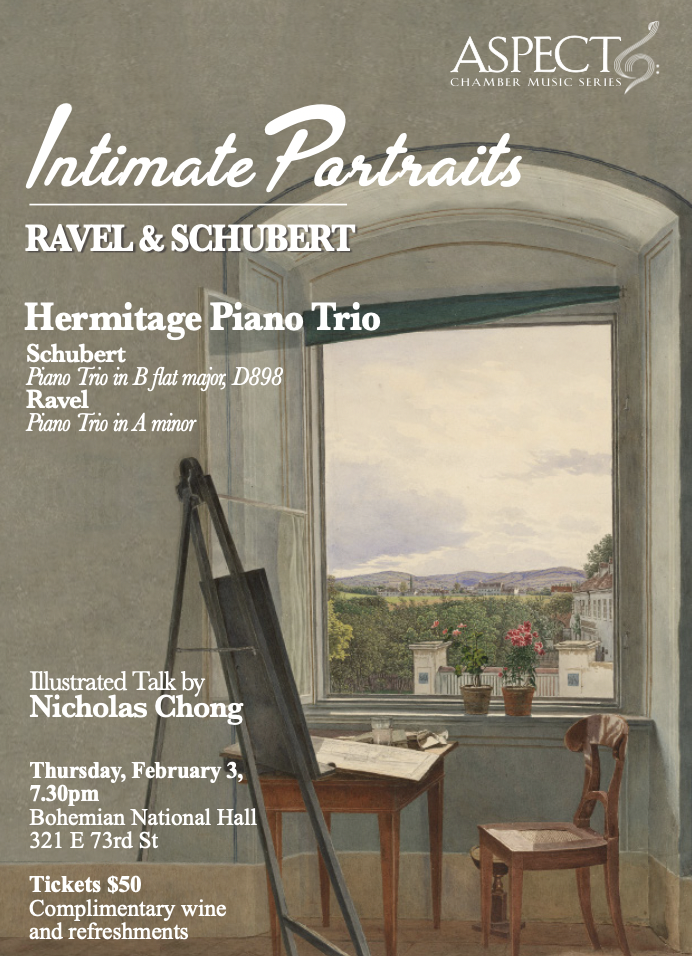

INTIMATE PORTRAITS: RAVEL & SCHUBERT

February 3, 2022 | Bohemian National Hall

Hermitage Piano Trio

Illustrated Talk by Nicholas Chong

PROGRAM

Schubert Piano Trio in B flat major, D898

Ravel Piano Trio in A minor

Photographs by Tao Ho © 2022

When it comes to love, both Maurice Ravel and Franz Schubert are enigmas. Their music can be so tender, so delicately sensuous, so touchingly intimate, and yet nobody knows if either had relationships in the modern sense of the word. Was there an element of yearning for an impossible ideal in both men? Did they privately enjoy the sweet sorrow of unfulfilled longing, or were there darker, more painful secrets? Both of the exquisite piano trios in this concert can be enjoyed simply as glorious outpourings of song and dance, but there are complexities beneath their seductive surfaces, the kind of shadowy riddles and ambiguities which can haunt the mind long after the performance is over. Heard together, it’s possible that both trios may reveal more than these guarded composers apparently intended.