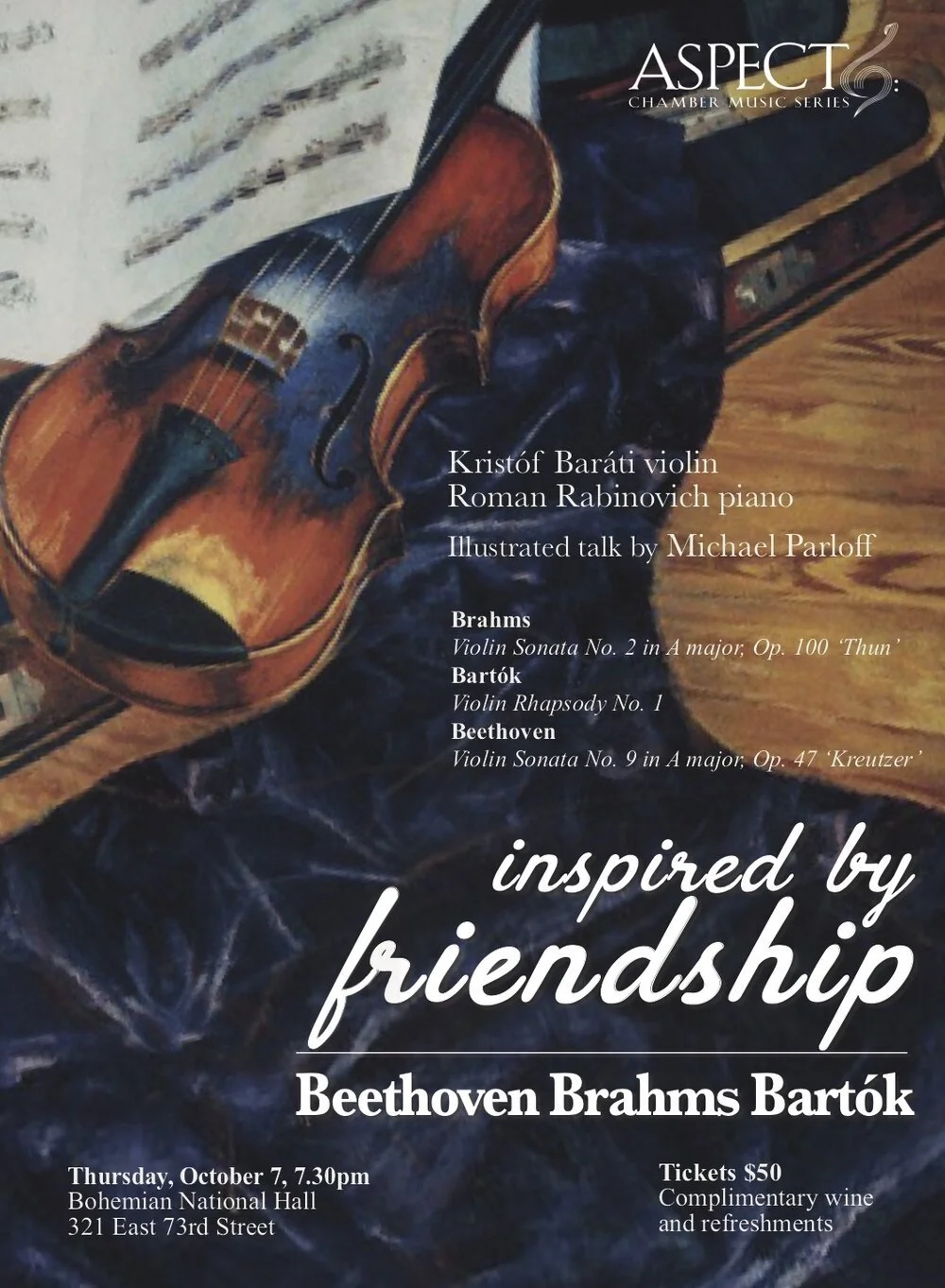

INSPIRED BY FRIENDSHIP

October 7, 2021 | Bohemian National Hall

Kristóf Baráti violin

Roman Rabinovich piano

Illustrated talk by Michael Parloff

PROGRAM

Brahms Violin Sonata No. 2 in A major, Op. 100 ‘Thun’

Bartók Violin Rhapsody No. 1

Beethoven Violin Sonata No. 9 in A major, Op. 47 ‘Kreutzer’

Photographs by Tao Ho © 2021

Great music has often flowered from friendships between like-minded artists. In 1803, Beethoven’s short-lived friendship with the charismatic Afro-European violinist George Polgreen Bridgetower inspired his tempestuous Violin Sonata in A major, Op. 47. Sadly, the two artists quarreled soon after the successful Viennese premiere – Bridgetower called it ‘a silly argument over a girl’ – and the mercurial composer summarily withdrew his dedication to his erstwhile friend and rededicated the sonata to the celebrated French violinist Rodolphe Kreutzer. Béla Bartók maintained a more durable friendship with his esteemed violinist colleague Joseph Szigeti. Their fruitful partnership yielded many remarkable works, including Bartók’s First Violin Rhapsody, dedicated to his friend and compatriot Szigeti. In the summer of 1886, the 53-year-old Brahms fell under the spell of the young contralto Hermine Spies. Inspired by her artistry and beauty, he composed songs for them to perform together at the idyllic Swiss resort of Thun. Later that summer, he wove themes from ‘her’ songs into the fabric of his radiant Violin Sonata No. 2 in A major, Op. 100.