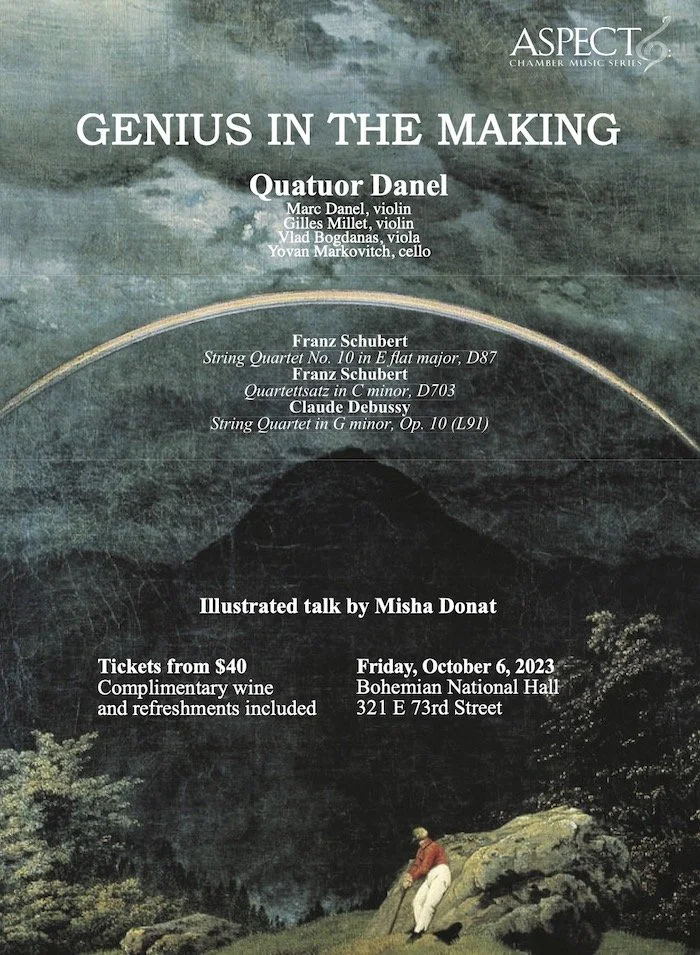

GENIUS IN THE MAKING

October 6, 2023 | Bohemian National Hall

Quatuor Danel

Illustrated talk by Misha Donat

Program

Schubert String Quartet No. 10 in E flat major, D87

Schubert Quartettsatz in C minor, D703

Debussy String Quartet in G minor, Op. 10 (L91)

Photographs by Alex Fedorov © 2023

As an immensely talented teenager, Schubert composed around a dozen string quartets which show his melodic style at its warmest and most generous, including No. 10 in E flat major. Some years later he began writing a more dramatic and intense quartet, but only managed to compose its first movement – the so-called ‘Quartettsatz’ in C minor – and part of a slow movement before setting the project aside. Debussy’s only string quartet belongs among his earliest important compositions. It reveals his acute ear for color, a gift which allied him with some of the foremost artists of the period: Monet would soon be at work on his famous series of water-lily paintings, while Cézanne was about to embark on his late landscapes of Mont Sainte-Victoire.