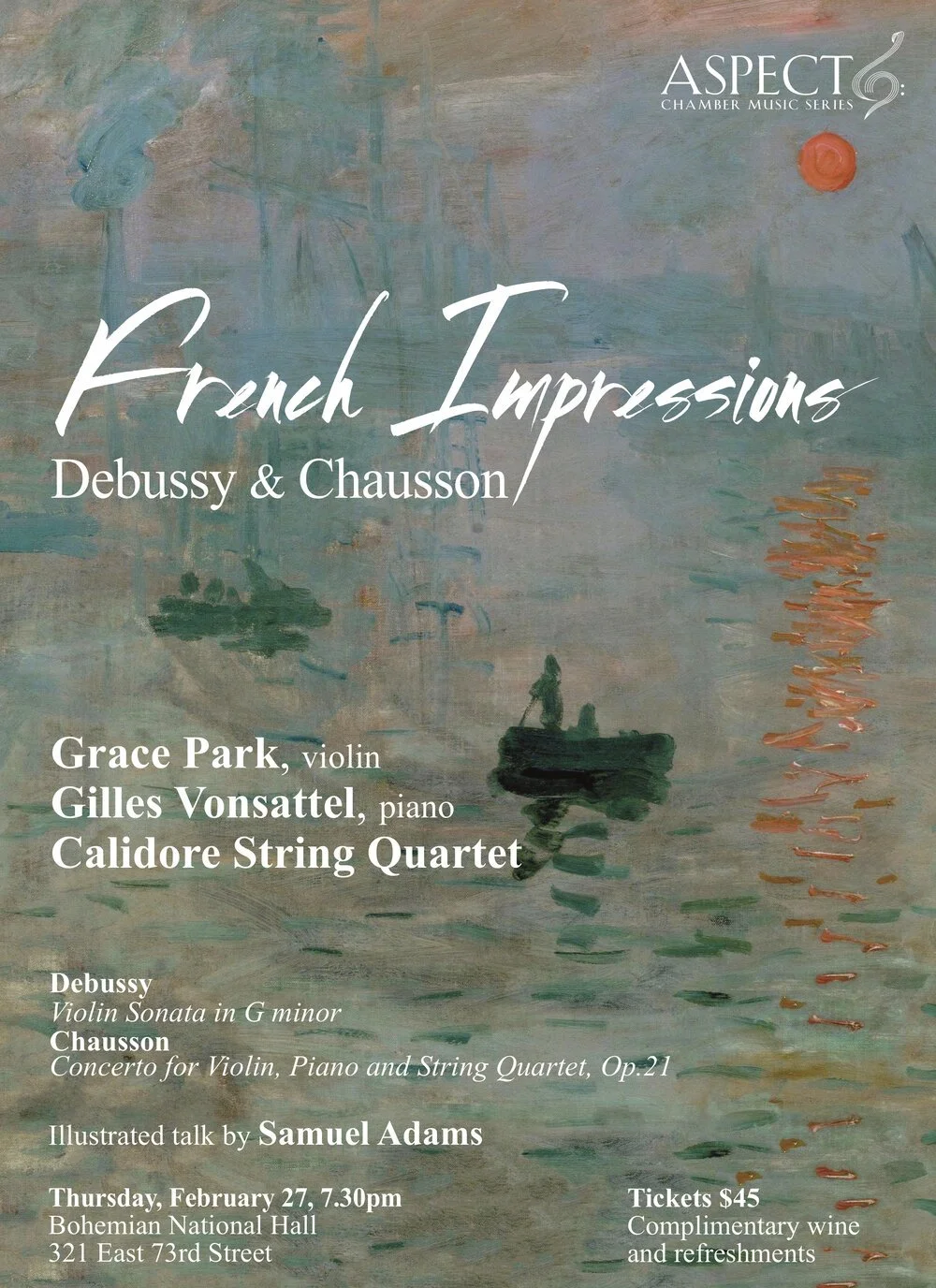

FRENCH IMPRESSIONS

February 27, 2020 | Bohemian National Hall

Grace Park violin

Gilles Vonsattel piano

Calidore String Quartet

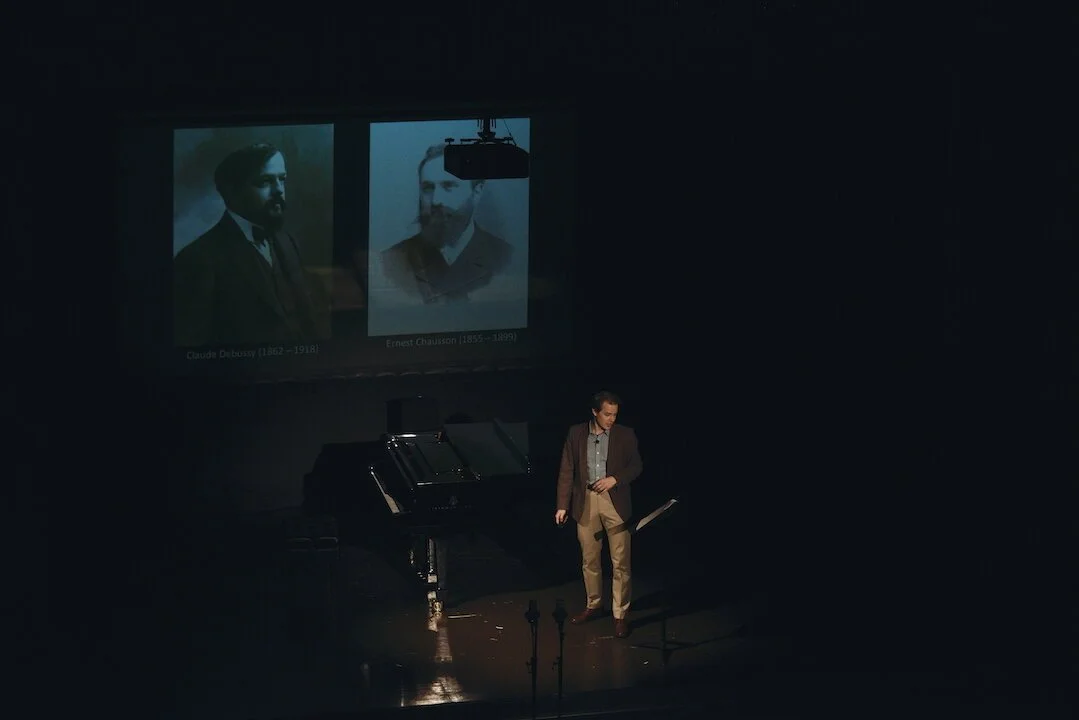

Illustrated talk by Samuel Adams

PROGRAM

Debussy Violin Sonata in G minor

Chausson Concerto for Violin, Piano and String Quartet, Op.21

In 1874, Claude Monet unveiled an en plein air painting depicting the port of Le Havre. It was this painting, Impression, Sunrise, that gave birth to Impressionism, both the movement and the name. Though Claude Debussy’s music is often compared with the works of Monet – that other great French Claude – Impressionism in music and painting have little in common, other than the perceived dissolution of form attributed to both art forms.

Both Debussy and Chausson were passionate about the visual arts – between giving up his legal profession and devoting himself to music Chausson even considered becoming an artist. Yet the two men reacted quite differently to the Impressionist movement. While Debussy drew upon a vast range of visual sources for his orchestral and other instrumental works (from Watteau via Turner to Gustave Moreau), Chausson appears not to have relied upon either literary or visual inspiration for his music. He was a rather conservative composer who, in the age of Ravel and Stravinsky, seemed more drawn to the Romantic tradition of César Franck.