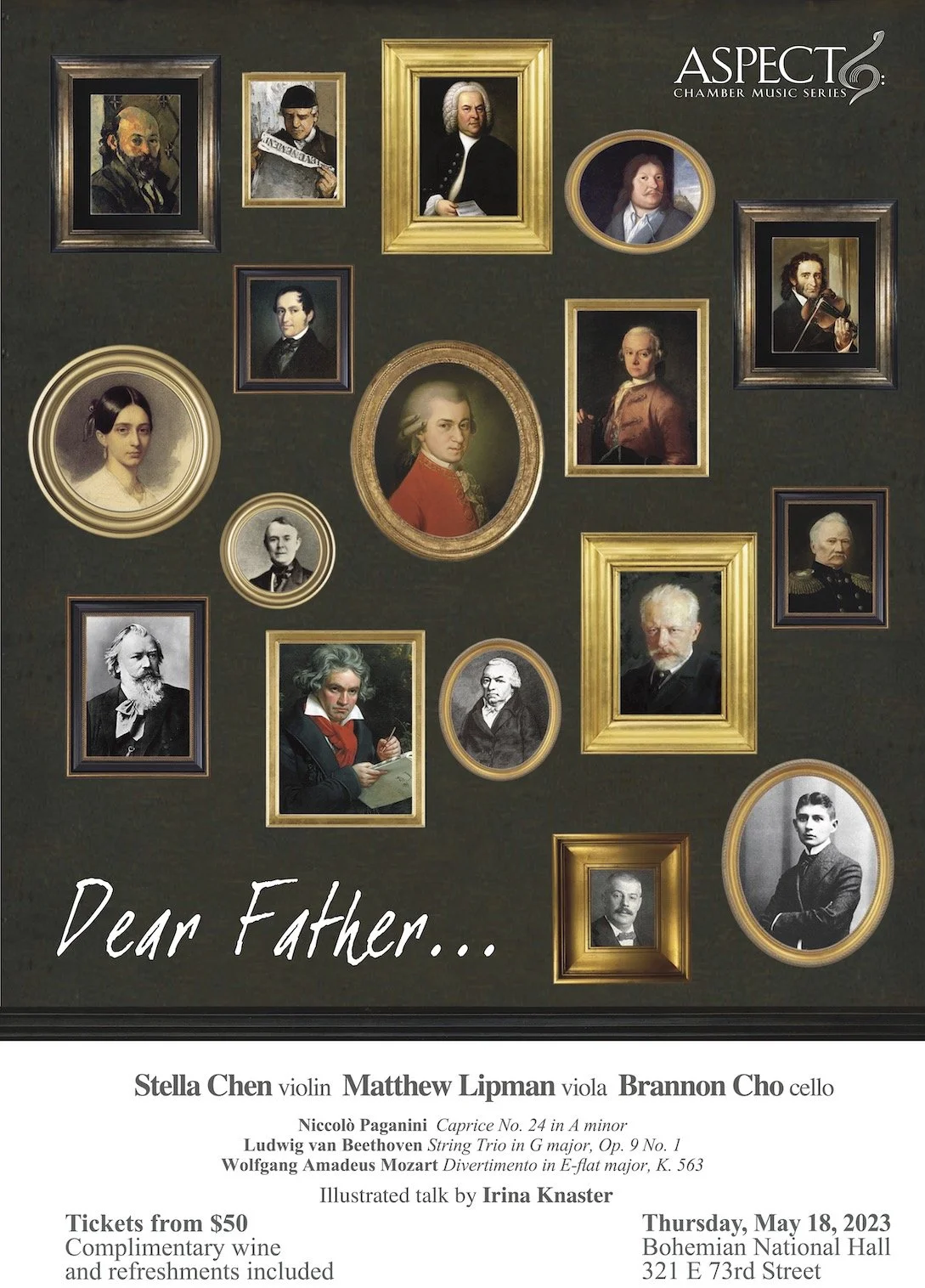

DEAR FATHER…

May 18, 2023 | Bohemian National Hall

Stella Chen violin

Brannon Cho cello

Matthew Lipman viola

Illustrated talk by Irina Knaster

Program

Paganini Caprice No. 24 in A minor

Beethoven String Trio in G major, Op.9 No.1

Mozart Divertimento for String Trio

Photographs by Alex Fedorov © 2023

An encouraging, musical father – perfect for a young composer, surely? But, as the old saying goes, be careful what you wish for. Nicolò Paganini’s father was delighted when he saw the sparks of future genius in his son, but a mixture of greed and frustrated ambition turned him into a tyrant whose treatment of the young virtuoso left deep scars. Mozart’s father Leopold was at first more genuinely encouraging, but his son’s vitality and sheer genius proved too much for him, and in the end only an act of outright rebellion set Wolfgang truly free. Beethoven’s father was a court musician, but he was also a drunken bully, who thought nothing of dragging young Ludwig out of bed in the middle of the night to play for his horrible cronies. In each case, however, it was, above all, a love of music that saved these composer-performers and set them on the path to glory. Somehow, they were able to become not what their fathers wanted, but what they were truly meant to be. We hear all three in full flower: Paganini in his ardent and dazzlingly difficult Fourth Caprice, Beethoven in his ambitious, almost symphonic String Trio, Op. 9 No. 1, and Mozart in his (deceptively) modestly titled Divertimento for string trio, in which just three instruments open up vistas on enchanting new worlds.