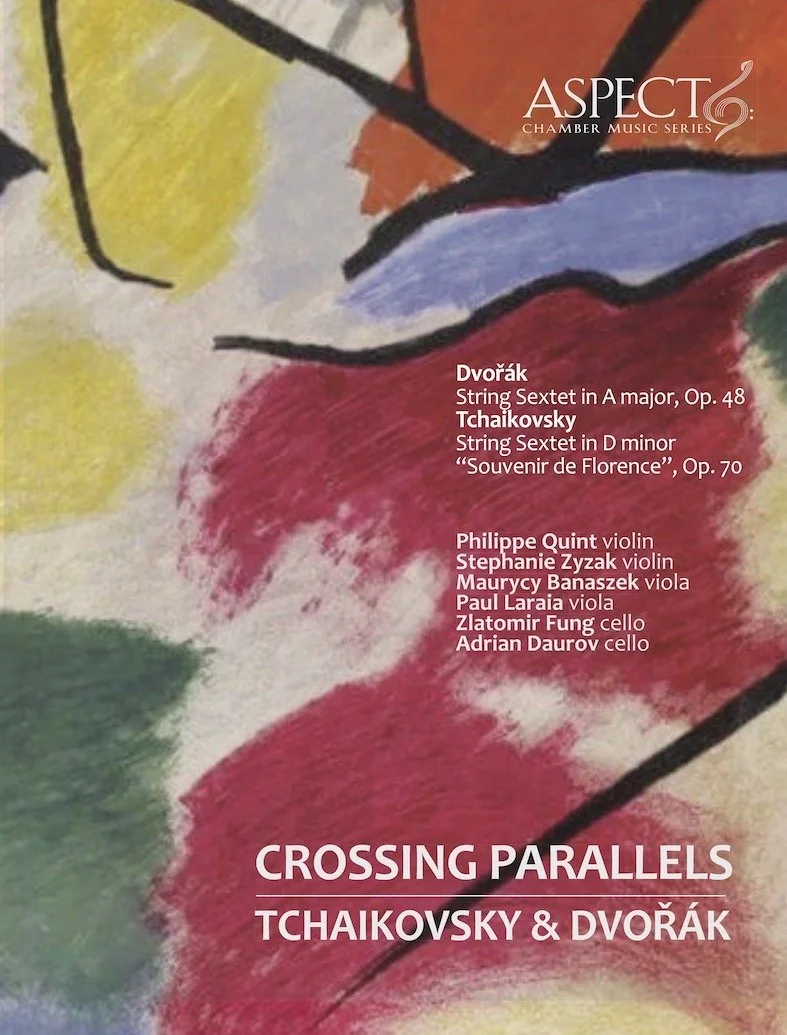

CROSSING PARALLELS: TCHAIKOVSKY & DVORAK

December 7, 2022 | Bohemian National Hall

Philippe Quint violin

Stephanie Zyzak violin

Maurycy Banaszek viola

Paul Laraia viola

Zlatomir Fung cello

Adrian Daurov cello

Illustrated talk by Irina Knaster

PROGRAM

Dvořák String Sextet in A major, Op. 48

Tchaikovsky String Sextet in D minor "Souvenir de Florence", Op. 70

Photographs by Alex Fedorov © 2022

In their own homelands, Tchaikovsky and Dvořák are national heroes, treasured for giving musical voice to their native cultures with special warmth and authority. But there was nothing narrow or exclusive about their ‘nationalism’. Tchaikovsky’s gorgeous Sextet ‘Souvenir de Florence’ could be subtitled ‘A Russian in Italy’. It radiates love for the sunlit Mediterranean lands, echoes street dances and serenades, and evokes the eerie magic of summer lightning. But all this sits comfortably alongside Russian folk-like tunes – a sense of national selfhood can be enriched by contact with other peoples and their cultures. Dvořák wrote his Sextet around the same time as his sensationally successful first set of Slavonic Dances, and like them it speaks eloquently of his attachment to Czech song and dance, and to the luscious rolling landscapes of his native Bohemia. But it also shows him at home with the cosmopolitan style of Western European music, embodied by his new friend, the German Meister Johannes Brahms. Both works are proof that you can be both national and international, sing of home while flinging wide your embrace to take in all humanity.