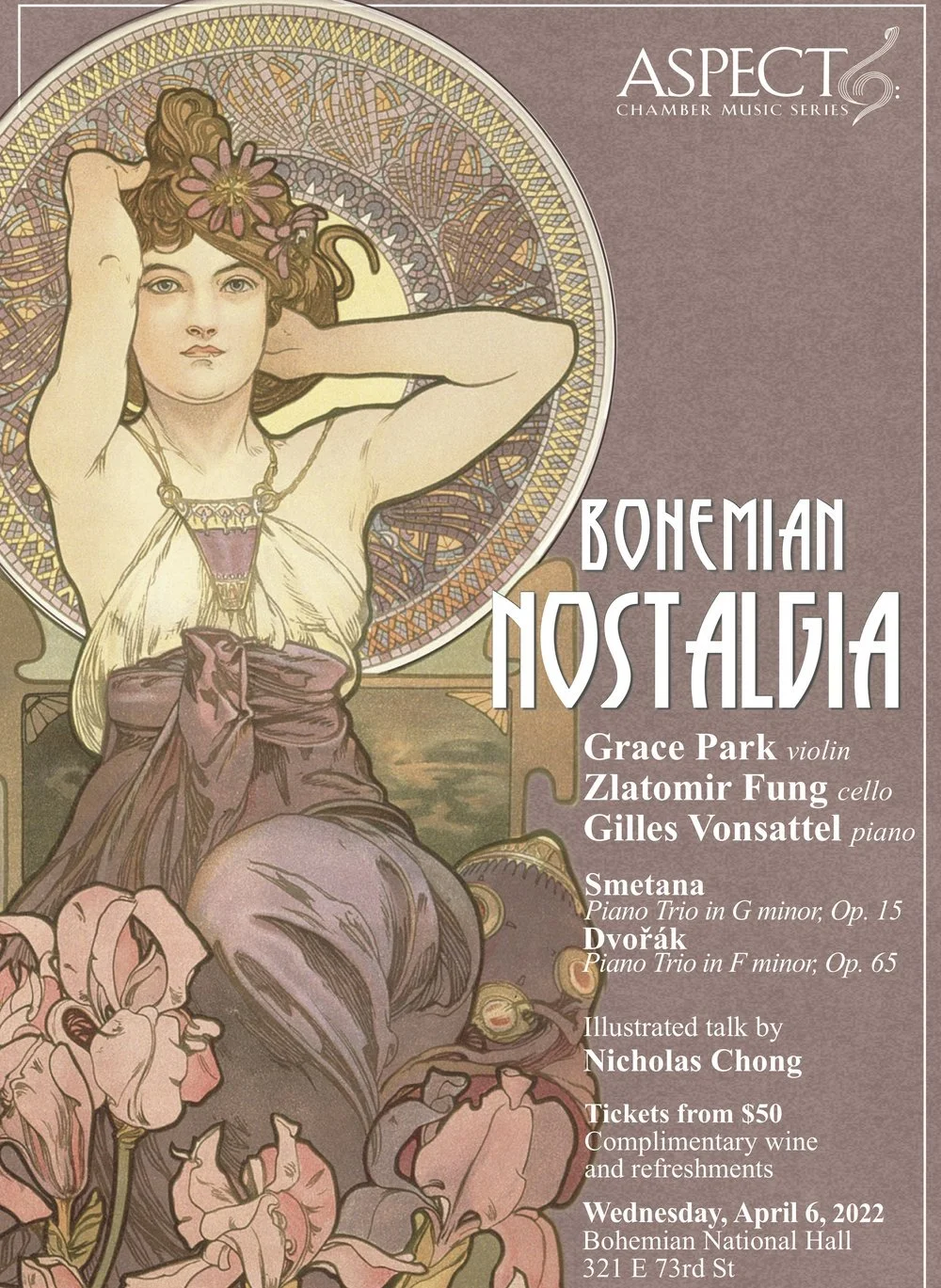

BOHEMIAN NOSTALGIA

April 6, 2022 | Bohemian National Hall

Grace Park violin

Zlatomir Fung cello

Gilles Vonsattel piano

Illustrated talk by Nicholas Chong

PROGRAM

Smetana Piano Trio, Op. 15

Dvořák Piano Trio No.3, Op. 65

Photographs by Tao Ho © 2022

The ancient kingdom of Bohemia has a history of cultural riches and turbulent politics. The nineteenth century brought relative stability – but at a cost. Bohemia was now subsumed into the complex but firmly-administered entity of Habsburg Austria, with German as its official language. As a member of the Bohemian bourgeoisie, Bedřich Smetana had to learn the Czech language and folk traditions and, like many of his class, he yearned to be reconnected with what he came to see as his true native culture. Dreams of an independent future were rooted in treasured images of the country’s great past, so nostalgia paradoxically became a tool for politically progressive thinking. Intense melancholy and lively folk-coloured dance music alternate in Smetana’s impassioned Piano Trio, in a manner which sometimes recalls the national dance known as the dumka, in which exhilaration and reflective sadness are often starkly juxtaposed. By contrast, Antonín Dvořák was born with both the Czech language and Bohemian music in his blood, as is warmly reflected in the generous lyricism and rhythmic energy of his Third Piano Trio. Yet there are moments in this work too which seem to look back longingly to some kind of vanished Eden: Bohemia’s golden age? Youthful love lost? It’s hard to tell, yet there remains something mysteriously, touchingly ‘national’ about this very particular brand of Slavic melancholy.