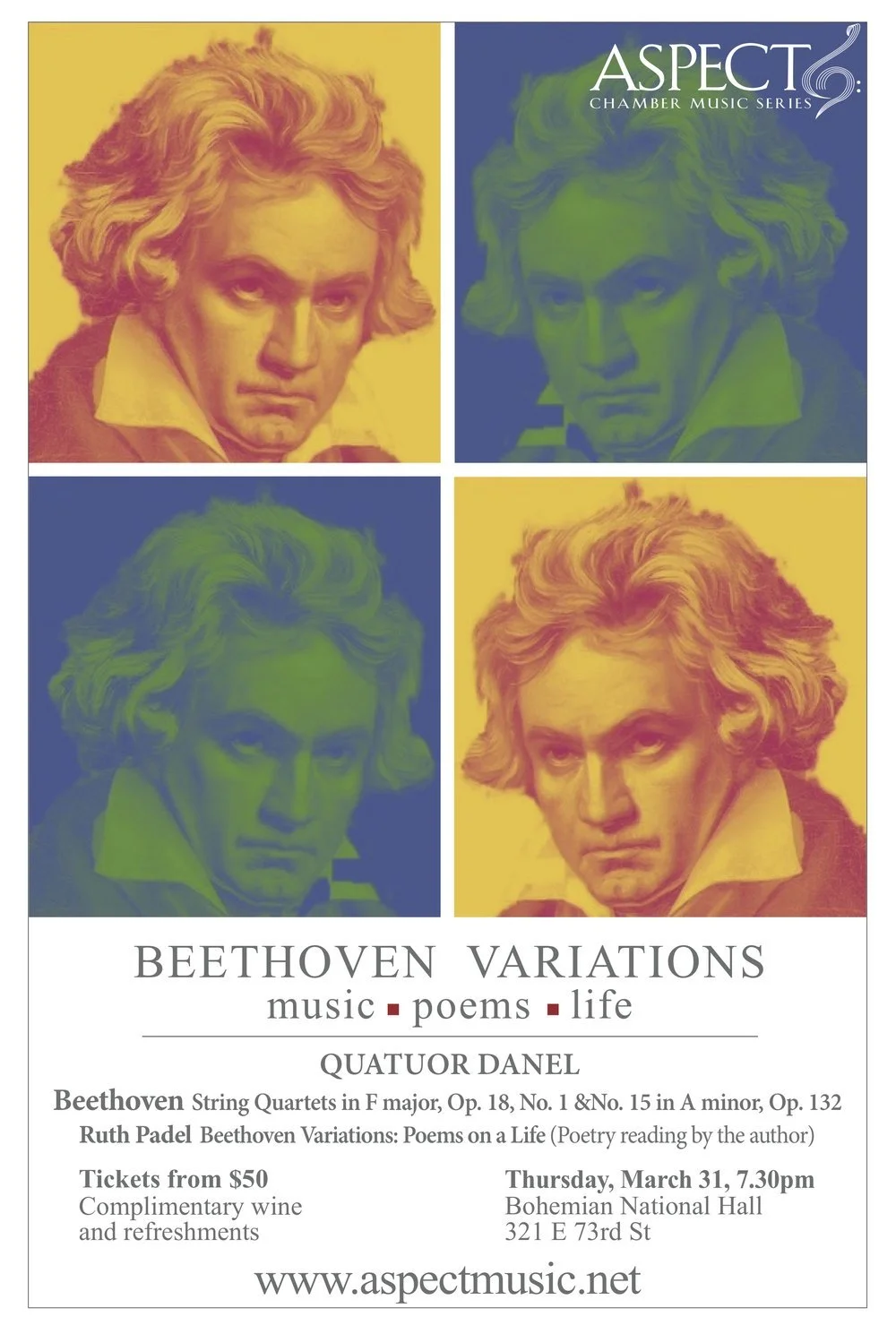

BEETHOVEN VARIATIONS

March 31, 2022 | Bohemian National Hall

Quatuor Danel

Ruth Padel Beethoven Variations: Poems on a Life

Poetry reading by the author

PROGRAM

Beethoven String Quartet in F major, Op. 18, No. 1

Beethoven String Quartet No. 15 in A minor, Op. 132

Photographs by Tao Ho © 2022

This unique concert featured Ruth Padel’s biographical poetry about Beethoven alongside performances of two of the composer’s string quartets. The first of these – the impetuous, impassioned and brilliant Op. 18 No. 1 – was written in around 1800 when Beethoven was thirty, while the second – the sublime Op. 132 – was finished in 1825, only two years before he died. How did this lonely, haunted man distill his extraordinary life journey into the quartet form, one full of conversation, human togetherness, social harmony, and integration? How did he move from the Classical balance of the six Op. 18 works to the dark, haunting beauty of Op. 132, with its contemplative central Molto adagio? Ruth Padel, an award-winning British poet and scholar, has created a lyrical journey through Beethoven’s life, family, feelings and music. She reada selection of poems that illuminated the life and thought behind the two quartets performed by the extraordinary Quatuor Danel.